Recent Bankruptcies Signal Shakiness in Credit Markets

The high-profile collapses of First Brands Group (a global auto-parts supplier) and Tricolor Holdings (a subprime auto lender) have stirred some alarm amongst investors. The central question investors are asking is: are these isolated failures, or early warnings of deeper credit stress?1

I think the answer lies somewhere in the middle.

First Brands’ bankruptcy is a striking story. The company, once an industrial roll-up boasting 26,000 employees and a portfolio spanning 25 well-known automotive brands, borrowed over $10 billion from a mix of Wall Street lenders and private funds. But as new directors and forensic accountants now sift through its books, they’ve uncovered what appears to be $2 billion in unaccounted-for funds and billions more in off–balance sheet borrowing. 2

From my vantage, it appears that exposure to First Brands’ bad loans is spread across dozens of banks and collateralized loan obligation (CLO) funds, which is actually a good thing. It means no one institution’s holdings are likely large enough to trigger contagion. Even still, it’s a sharp reminder of the lack of transparency that has crept into parts of the private debt market, now approaching $2 trillion in size. It is relatively common to see these types of credit quality issues creep up near the end of an easy money environment. Increased risk aversion for debt investors who have been searching for yield would be appropriate in response to the First Brands’ bankruptcy.

What the Latest Market Data Means for Q4 Positioning

With markets at record highs and valuation concerns mounting, investors need a clear view of what’s driving performance.

The October Stock Market Outlook Report3 examines earnings strength, sector leadership, and key economic signals to help you assess whether current prices are justified or vulnerable.

Inside, you’ll find the critical data and analysis investors are using to position for Q4, such as:

- Asset allocation guidelines for today’s market environment

- Expert forecasts for inflation, rates, and economic trends

- Industry tables and rankings to help you spot opportunities

- Buy-side and sell-side consensus insights at a glance

- And much more!

If you have $500,000 or more to invest, claim your free copy of the report and see how today’s policy shifts could shape tomorrow’s opportunities.

IT’S FREE. Download our latest October Stock Market Outlook Report3

Then there’s Tricolor Holdings, a Texas-based subprime auto lender that targeted borrowers without credit histories or documentation. It filed for liquidation last month, listing more than $1 billion in liabilities. The business model, based on “buy here, pay here” auto sales financed through asset-backed securities, crumbled under rising delinquencies and tighter funding conditions. Now, some tranches of Tricolor’s securitized debt that once traded above par are only worth pennies on the dollar.

Taken together, these bankruptcies show how weaker players at the fringes of the credit spectrum are struggling. Years of easy liquidity and investor demand for yield have encouraged aggressive underwriting. As the economy normalizes and interest rates settle above the near-zero era, some of those bets are now being tested.

The private credit market, in particular, is where I’m increasingly turning my focus. Defaults in business development companies (BDCs) and other private-lending vehicles have been creeping higher. Roughly 11% of loans in these portfolios now pay interest “in kind”, that is, with IOUs instead of cash—signaling stress among smaller borrowers. Fitch’s measure of private credit defaults hit 9.5% this summer before easing slightly.

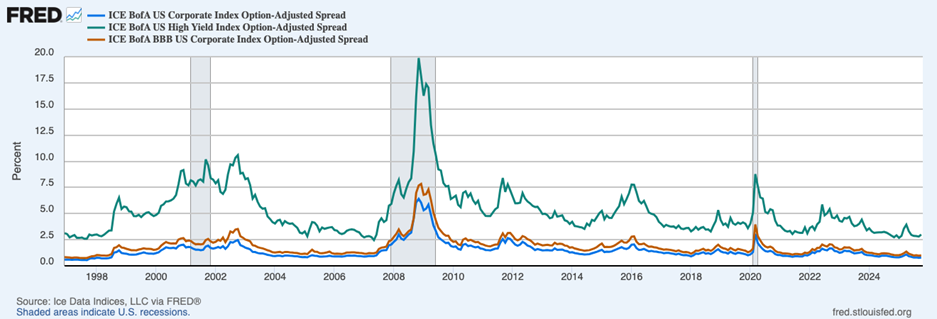

This is a market and a trend worth monitoring very closely. As I write, however, I think it’s important to qualify that “higher defaults” does not mean “credit crisis.” Public credit markets, the most transparent barometer of corporate financial health, aren’t showing much strain. High-yield bond defaults remain near 1%, well below their long-term average of around 4%. And investment-grade and high-yield spreads, as seen in the chart below, remain historically tight. Investors aren’t demanding higher risk premiums, which suggests the market is still confident that these issues are more local than systemic.

Credit Spreads Remain Subdued for Now, Even on the Riskier End of the Spectrum

The takeaway for investors, in my view, is to acknowledge that credit markets are running hot. The additional yield investors receive for holding corporate debt versus Treasurys has fallen to near 25-year lows, prompting companies to issue debt at record levels. This strength underscores confidence in the market, but it could also signal investor complacency. It’s important to constantly try to differentiate between the two.

Bottom Line for Investors

If I could sum this story up in a single sentence, it would be this: Remember that easy money often sows the seeds of future problems.

Or put in an even simpler way: bad loans are often made in good times.

The failures of First Brands and Tricolor are cautionary tales, and I think they warrant greater investor attention. They remind us that in the far reaches of the private and subprime credit universe, excesses built up during the era of cheap money are still unwinding. Investors should watch these developments closely, but also be careful not to overreact. Evidence from broader credit markets, like tight spreads, low defaults, and contained fallout, does not point to systemic stress, at least not yet.

Markets may be at record highs, but the real insight lies beneath the surface in profit trends, margin pressure, and revisions that shape future returns. Staying informed means focusing on data rather than distractions.

The October Stock Market Outlook5 breaks down the numbers guiding institutional decisions going into Q4. Inside, you’ll find:

- Asset allocation guidelines for today’s market environment

- Expert forecasts for inflation, rates, and economic trends

- Industry tables and rankings to help you spot opportunities

- Buy-side and sell-side consensus insights at a glance

- And much more!

Download your copy to cut through political noise and see the fundamentals shaping the market’s next move.

Disclosure

2 Wall Street Journal. September 29, 2025. https://www.wsj.com/finance/the-credit-market-is-hummingand-that-has-wall-street-on-edge-0721c324?mod=Searchresults&pos=4&page=1

3 Zacks Investment Management reserves the right to amend the terms or rescind the free-Stock Market Outlook Report offer at any time and for any reason at its discretion.

4 Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BAMLC0A0CM#

5 Zacks Investment Management reserves the right to amend the terms or rescind the free-Stock Market Outlook Report offer at any time and for any reason at its discretion.

DISCLOSURE

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Inherent in any investment is the potential for loss.

Zacks Investment Management, Inc. is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Zacks Investment Research. Zacks Investment Management is an independent Registered Investment Advisory firm and acts as an investment manager for individuals and institutions. Zacks Investment Research is a provider of earnings data and other financial data to institutions and to individuals.

This material is being provided for informational purposes only and nothing herein constitutes investment, legal, accounting or tax advice, or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a security. Do not act or rely upon the information and advice given in this publication without seeking the services of competent and professional legal, tax, or accounting counsel. Publication and distribution of this article is not intended to create, and the information contained herein does not constitute, an attorney-client relationship. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment or strategy is suitable for a particular investor. It should not be assumed that any investments in securities, companies, sectors or markets identified and described were or will be profitable. All information is current as of the date of herein and is subject to change without notice. Any views or opinions expressed may not reflect those of the firm as a whole.

Any projections, targets, or estimates in this report are forward looking statements and are based on the firm’s research, analysis, and assumptions. Due to rapidly changing market conditions and the complexity of investment decisions, supplemental information and other sources may be required to make informed investment decisions based on your individual investment objectives and suitability specifications. All expressions of opinions are subject to change without notice. Clients should seek financial advice regarding the appropriateness of investing in any security or investment strategy discussed in this presentation.

Certain economic and market information contained herein has been obtained from published sources prepared by other parties. Zacks Investment Management does not assume any responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of such information. Further, no third party has assumed responsibility for independently verifying the information contained herein and accordingly no such persons make any representations with respect to the accuracy, completeness or reasonableness of the information provided herein. Unless otherwise indicated, market analysis and conclusions are based upon opinions or assumptions that Zacks Investment Management considers to be reasonable. Any investment inherently involves a high degree of risk, beyond any specific risks discussed herein.

The S&P 500 Index is a well-known, unmanaged index of the prices of 500 large-company common stocks, mainly blue-chip stocks, selected by Standard & Poor’s. The S&P 500 Index assumes reinvestment of dividends but does not reflect advisory fees. The volatility of the benchmark may be materially different from the individual performance obtained by a specific investor. An investor cannot invest directly in an index.