Not long ago, the notion of spending trillions of dollars on an economic plan or a government budget would have raised many eyebrows. Today, it seems like spending trillions is just part of the daily discourse – not only for the U.S. government, but also for governments abroad.

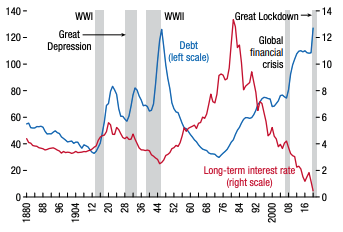

In the wake of the pandemic, global government debt has swelled to its highest level since World War II. Global debt is so high, in fact, that it exceeds global output (GDP). Indeed, global government debt rose to 105% of global GDP in 2020, up from 88% in 2019.1

The International Monetary Fund created a useful graphic to track global debt levels (blue line) since 1880. As you can see, World War II was the last time the world was anywhere near current debt levels, and debt-to-GDP dropped off substantially when the war ended.

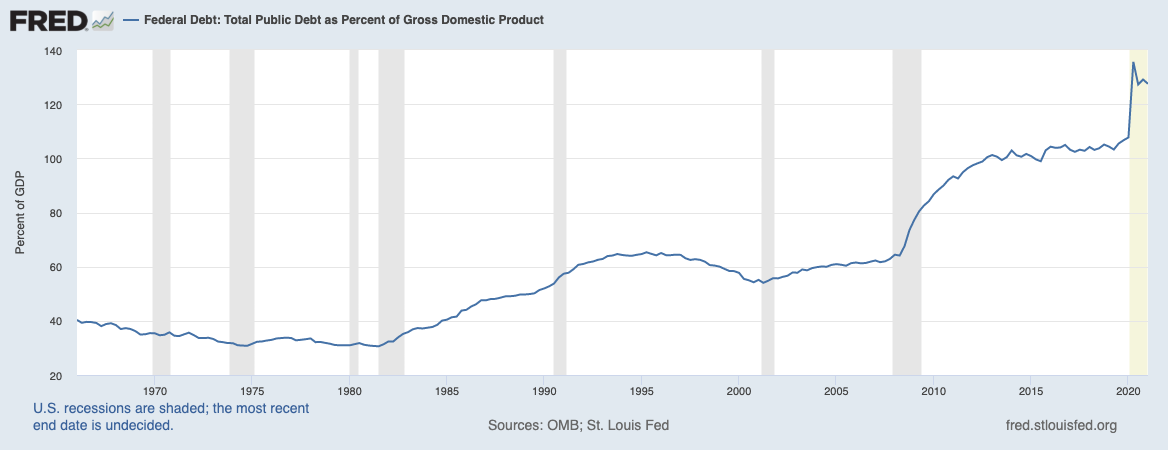

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis2

Here in the U.S., the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis has charted federal public debt as a percent of GDP since 1966, which you can also see is very high relative to recent history. The debt issue will not get any better this year, either – the U.S. government is on track for a budget deficit of $3 trillion for the second year in a row, which does not even factor current spending plans making their way through Congress.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis3

So, why is this global swell of borrowing happening, and what does it mean for markets and investors?

Let’s start with the ‘why.’ Jump-starting the post-pandemic economic recovery is of course a big driver of new spending. But behind this spending is the memory of a lackluster recovery in the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, where many developed countries believe they did not spend enough and where fiscal austerity – particularly in Europe – started too quickly. Another popular economic theory is that aging populations, high savings, and weak private investments are creating slack in developed economies, and governments are increasingly stepping in with spending to boost overall output.

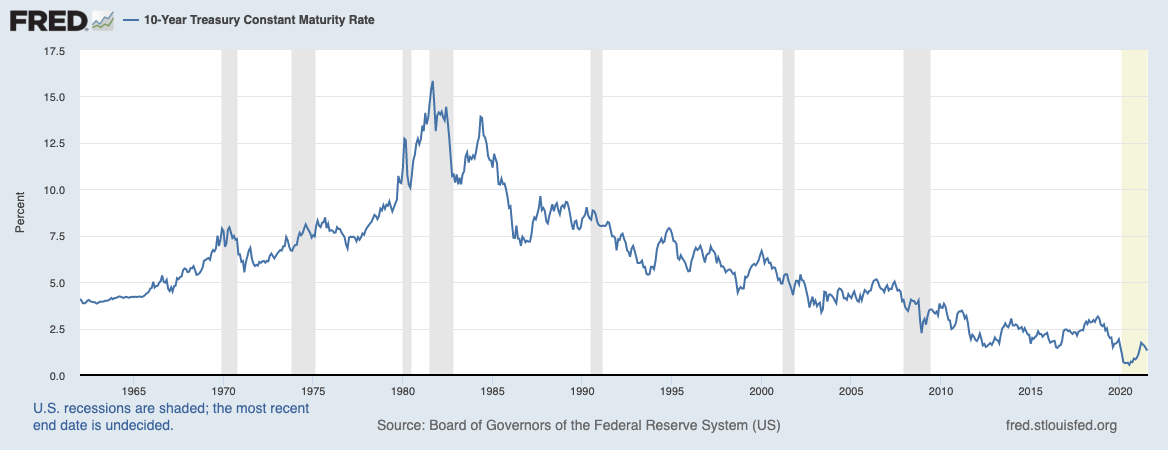

But perhaps the biggest driver of rising debt loads has to do with cost. As government debt has become – and remained – inexpensive, it has also grown in size substantially. Even as budget deficits swell and total debt rises, the cost of borrowing in the U.S. (as measured by U.S. Treasury bond yields) has remained historically low. The government has passed multiple trillion-plus dollar stimulus packages, and yet the yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury remains well below 2%. In other words, the U.S. continues to issue debt at a very low cost.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis4

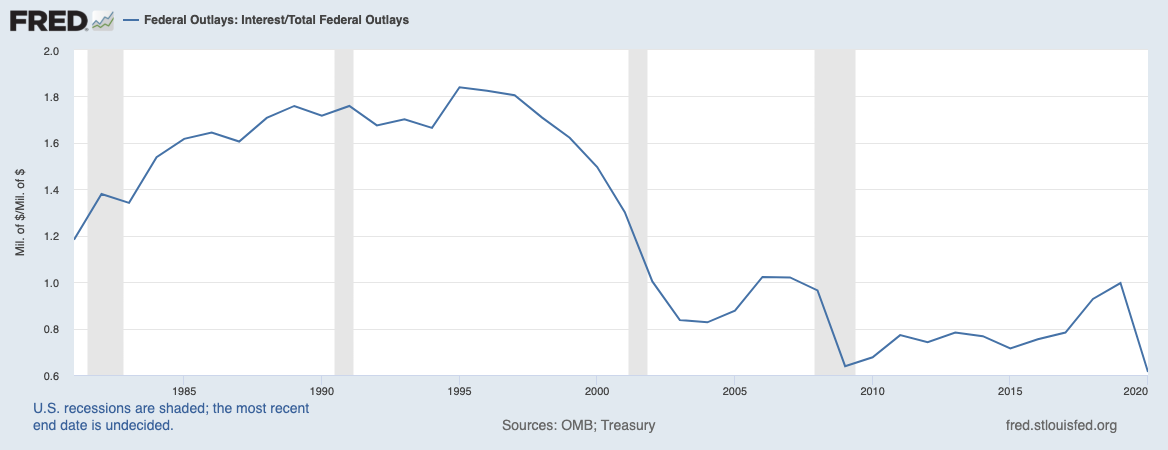

Long duration bond yields tell us about interest rates on new debt, but another key metric to observe is how much the federal government is spending on debt (interest payments) as a percentage of total federal spending. In other words, if federal spending was increasingly going to make interest payments on debt – instead of spending directly in the economy – then there would be reasonable cause for major concern. But we are not seeing that today. The ratio of interest payments to total spending is also historically low:

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis5

Just because borrowing and debt-servicing costs are modest does not mean rising debt levels are risk-free or even low risk. There are plenty of reasons to look forward cautiously. Inflationary pressures, which we are seeing currently here in the U.S. and abroad, can push interest rates higher over time. If interest on debt ever exceeds a country’s GDP growth rate, it could spell trouble for debt-servicing costs and maybe force a government to raise taxes or allow inflation to ease the debt burden – neither of which is a good outcome.

Bottom Line for Investors

Government spending is in the formula for calculating GDP. When government spending goes up, it’s a positive contributor to total output. This is not to say government spending always creates a multiplier effect or leads to increases in growth and productivity. Many would argue the opposite is true, which is another topic for another day.

There are issues with too much government borrowing and spending. Inflation can become an issue, interest rates can go up, and the private sector can be crowded out of financing and investing. At worst, if the government is picking winners and losers with spending, the private sector may respond by pulling back on investment in areas where the government is too big of a force.

The key to debt sustainability is having growth higher than interest rates. If an economy can grow faster than the interest rate paid on debt, then there is a good chance the debt will be manageable. This is the current situation in the U.S., but it may change in the not-too-distant future.

Disclosure

2 International Monetary Fund. April 2021. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2021/03/29/fiscal-monitor-april-2021

3 Fred Economic Data. June 24, 2021. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GFDEGDQ188S

4 Fred Economic Data. July 16, 2021. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS10

5 Fred Economic Data. June 29, 2021. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FYOINT

DISCLOSURE

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Inherent in any investment is the potential for loss.

Zacks Investment Management, Inc. is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Zacks Investment Research. Zacks Investment Management is an independent Registered Investment Advisory firm and acts as an investment manager for individuals and institutions. Zacks Investment Research is a provider of earnings data and other financial data to institutions and to individuals.

This material is being provided for informational purposes only and nothing herein constitutes investment, legal, accounting or tax advice, or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a security. Do not act or rely upon the information and advice given in this publication without seeking the services of competent and professional legal, tax, or accounting counsel. Publication and distribution of this article is not intended to create, and the information contained herein does not constitute, an attorney-client relationship. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment or strategy is suitable for a particular investor. It should not be assumed that any investments in securities, companies, sectors or markets identified and described were or will be profitable. All information is current as of the date of herein and is subject to change without notice. Any views or opinions expressed may not reflect those of the firm as a whole.

Any projections, targets, or estimates in this report are forward looking statements and are based on the firm’s research, analysis, and assumptions. Due to rapidly changing market conditions and the complexity of investment decisions, supplemental information and other sources may be required to make informed investment decisions based on your individual investment objectives and suitability specifications. All expressions of opinions are subject to change without notice. Clients should seek financial advice regarding the appropriateness of investing in any security or investment strategy discussed in this presentation.

Certain economic and market information contained herein has been obtained from published sources prepared by other parties. Zacks Investment Management does not assume any responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of such information. Further, no third party has assumed responsibility for independently verifying the information contained herein and accordingly no such persons make any representations with respect to the accuracy, completeness or reasonableness of the information provided herein. Unless otherwise indicated, market analysis and conclusions are based upon opinions or assumptions that Zacks Investment Management considers to be reasonable. Any investment inherently involves a high degree of risk, beyond any specific risks discussed herein.

The S&P 500 Index is a well-known, unmanaged index of the prices of 500 large-company common stocks, mainly blue-chip stocks, selected by Standard & Poor’s. The S&P 500 Index assumes reinvestment of dividends but does not reflect advisory fees. The volatility of the benchmark may be materially different from the individual performance obtained by a specific investor. An investor cannot invest directly in an index.

The MSCI ACWI captures large and mid-cap representation across 23 Developed Markets (DM) and 27 Emerging Markets (EM) countries. With 2,986 constituents, the index covers approximately 85% of the global investable equity opportunity set. An investor cannot invest directly in an index. The volatility of the benchmark may be materially different from the individual performance obtained by a specific investor.

The MSCI UK All Cap Index captures large, mid, small and micro-cap representation of the UK market. With 819 constituents, the index is comprehensive, covering approximately 99% of the UK equity universe. An investor cannot invest directly in an index. The volatility of the benchmark may be materially different from the individual performance obtained by a specific investor.