Valuations are Important to Watch, But They’re Not Timing Tools

Many investors are worried about valuations at current levels.

Even as some of the biggest players in the Technology sector continue to deliver strong earnings and revenue growth, the powerful rally has pushed multiples above historical norms and caused some concern about the possibility of a bubble.

The goal of this week’s column is not to tell you to dismiss these concerns altogether. To put it bluntly, the U.S. equity market is not cheap and expectations for future earnings growth are high. Valuations across several areas—and large-cap growth in particular—are well above long-term averages. With the AI-driven trade, market leadership is also concentrated, which generally opens the door for elevated volatility. Investor attention is indeed warranted.1

But attention is not the same as timing. Historically, using valuation levels as a market-timing tool has not resulted in much success.

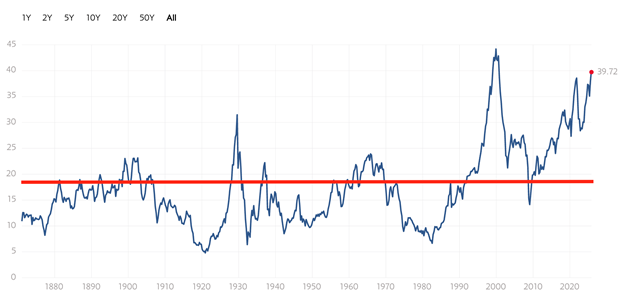

That’s because high valuations can tell us stocks have risen a lot, but that’s something investors already know. What valuations do not do a good job of telling us is where markets go next. Since 2010, for example, the often-lauded CAPE ratio has not had a single month where it was ‘below average’, but the stock market returned roughly 14% annualized during that decade. Zooming out even further, the U.S. stock market has been overvalued 95% of the time (according to the CAPE ratio measure) since 1990, but it’s delivered roughly 10% annualized returns since that time.

Shiller CAPE Ratio, 1870 – Present

My last word on the CAPE ratio is to remind investors that its fundamental flaw, in my view, is that it leans entirely on backward-looking earnings, many of which occurred years ago under different economic conditions. Stocks don’t price the past—they price what investors believe the next several years will bring. Valuations can remain above average for years, as long as earnings keep rising and investors remain willing to pay more for each dollar of profit.

At the end of the day, elevated valuations can set the stage for greater volatility or more uneven returns. The last few weeks in the tech sector are a case-in-point: otherwise strong companies saw sharp drawdowns simply because expectations had been stretched so far. When markets concentrate too much on a specific theme, the pullbacks can be swift. I think it’s important to acknowledge that point.

A more important point to acknowledge is that long-term investors do not need to predict when these types of swings will happen. Timing markets based on valuation has historically been a poor strategy. ‘Expensive’ markets can stay expensive, and expensive markets can keep rising as long as earnings keep going up. What matters far more than any single valuation metric is the market’s broader context—earnings trends, credit conditions, corporate profitability, labor market dynamics, and investor sentiment. And on those metrics, I would argue the picture of the U.S. economy is far from dire.

Bottom line for Investors

Parts of the U.S. market are unquestionably pricey today, but plenty of areas aren’t. Small caps, value-oriented sectors, and international stocks still trade at reasonable valuations and offer room for long-term growth. A diversified mix across styles and geographies helps prevent any one storyline, whether it’s the AI trade or something else, from driving your entire portfolio’s outcome.

The investor mistake we tend to see throughout history is not incorrectly owning an “expensive” market. It’s letting valuations alone dictate your decisions.

Disclosure

2 Multpl. November 18, 2025. https://www.multpl.com/shiller-pe

DISCLOSURE

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Inherent in any investment is the potential for loss.

Zacks Investment Management, Inc. is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Zacks Investment Research. Zacks Investment Management is an independent Registered Investment Advisory firm and acts as an investment manager for individuals and institutions. Zacks Investment Research is a provider of earnings data and other financial data to institutions and to individuals.

This material is being provided for informational purposes only and nothing herein constitutes investment, legal, accounting or tax advice, or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a security. Do not act or rely upon the information and advice given in this publication without seeking the services of competent and professional legal, tax, or accounting counsel. Publication and distribution of this article is not intended to create, and the information contained herein does not constitute, an attorney-client relationship. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment or strategy is suitable for a particular investor. It should not be assumed that any investments in securities, companies, sectors or markets identified and described were or will be profitable. All information is current as of the date of herein and is subject to change without notice. Any views or opinions expressed may not reflect those of the firm as a whole.

Any projections, targets, or estimates in this report are forward looking statements and are based on the firm’s research, analysis, and assumptions. Due to rapidly changing market conditions and the complexity of investment decisions, supplemental information and other sources may be required to make informed investment decisions based on your individual investment objectives and suitability specifications. All expressions of opinions are subject to change without notice. Clients should seek financial advice regarding the appropriateness of investing in any security or investment strategy discussed in this presentation.

Certain economic and market information contained herein has been obtained from published sources prepared by other parties. Zacks Investment Management does not assume any responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of such information. Further, no third party has assumed responsibility for independently verifying the information contained herein and accordingly no such persons make any representations with respect to the accuracy, completeness or reasonableness of the information provided herein. Unless otherwise indicated, market analysis and conclusions are based upon opinions or assumptions that Zacks Investment Management considers to be reasonable. Any investment inherently involves a high degree of risk, beyond any specific risks discussed herein.