Bond Yields are Rising Globally. Should Investors Be Concerned?

Bond markets aren’t known for volatility and tend to be viewed as a relatively boring, relatively stable component of capital markets. Stories over the past couple of weeks have suggested otherwise.

We’ve seen quite a bit of coverage concerning rising long-term government bond yields across the world. Notably, the 30-year U.S. Treasury brushed 5%, U.K. gilt yields reached their highest levels since 1998, and French yields hit multidecade peaks. Commentary about potential debt crises, inflation spirals, or even potential bailouts (France) followed shortly thereafter.

The spoiler alert here is that long duration bond yields have fallen back since, as has the media coverage about a potential crisis. But the unfolding of this story is worth a closer look, as it offers insights and takeaways for investors to keep in mind going forward.1

Take the U.S. narrative as an example. Some reports tied higher 30-year Treasury yields to fears about America’s fiscal trajectory, pointing out that interest costs on our country’s debt have ballooned and now exceed defense spending. In the U.K., coverage pointed to public finance concerns and a currency under pressure. France got its turn when a finance minister’s offhand comment about the IMF was spun into bailout speculation. And finally, Germany’s rising yields were tied to the cost and timing of its fiscal stimulus.

The key point for investors to notice is that each country’s rising yields came with their own unique explanation, but the broader story seemed to be missed completely. That is, that long duration yields were moving in tandem across developed markets. Even countries showing fiscal restraint, like Italy, saw their 30-year yield jump recently. The Netherlands, where debt is less than 50% of GDP, has experienced one of the biggest moves of all. Clearly, this isn’t about one country’s fiscal or inflation outlook.

So, what could have been a factor driving global bond yields higher? There’s no single answer, in my view, but there could be a few factors at play. Debt issuance has picked up after the summer lull, increasing supply. Seasonal patterns matter as well. September has historically been a weak month for long bonds, with global long-dated government debt posting a median loss of about 2% over the past decade. Finally, sentiment almost always plays a role. After years of near-zero interest rates and heavy central bank buying, investors have grown more sensitive to small shifts in expectations about growth, inflation, or policy. Long-term yields are where those expectations get expressed.

This is not to say that tariffs, inflation, or deficits are irrelevant. Tariff-driven price pressures have shown up modestly in recent inflation readings, and governments everywhere are contending with higher refinancing costs after borrowing heavily during the pandemic. But these are longer-term drags, not sudden shocks. The fact that yields are rising together across continents suggests the driver isn’t one country’s fiscal math, but rather a broad repricing of long-term debt globally. In short, something to keep an eye on but not panic over.

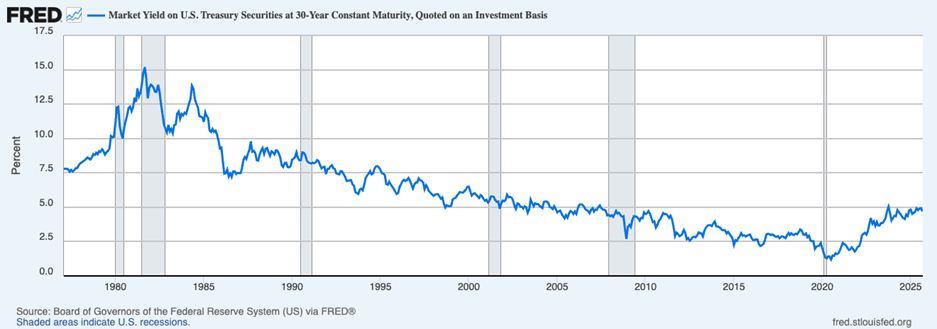

Perspective also helps. Looking at a 5-year chart of the U.S. 30-year Treasury bond yield shows a line moving steeply, up and to the right. But that’s only because yields were closer to 1.5% in 2020, which interest rates were at historic lows in the wake of the pandemic. Zooming out even further, it’s plain to see that today’s levels are low relative to previous decades.

U.S. 30-year Treasury Bond Yields

In fact, there may be positives here. With central banks cutting short-term rates and long yields drifting higher, yield curves are steepening, particularly outside the U.S. A steeper curve is a classic marker of healthier credit conditions, since it improves incentives for banks to lend. Rather than a warning sign, it may be an early indication that growth momentum is building, even if tariff and policy uncertainty continue to cloud the outlook.

Bottom Line for Investors

The ‘relatively stable, relatively boring’ expectation for bond markets can make sudden upticks uncomfortable, and it can also give rise to worrisome media narratives. But volatility in bond markets is normal. A few dozen basis points up or down doesn’t necessarily mark a crisis, and it’s not always necessary or constructive to require an explanation. Sometimes it’s just global markets adjusting and sentiment shifting.

As mentioned, the uptick in long-duration bond yields could even be construed as a positive for equity markets. A steepening yield curve often signals improving credit conditions, which could provide a growth tailwind looking ahead.

Disclosure

DISCLOSURE

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Inherent in any investment is the potential for loss.

Zacks Investment Management, Inc. is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Zacks Investment Research. Zacks Investment Management is an independent Registered Investment Advisory firm and acts as an investment manager for individuals and institutions. Zacks Investment Research is a provider of earnings data and other financial data to institutions and to individuals.

This material is being provided for informational purposes only and nothing herein constitutes investment, legal, accounting or tax advice, or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a security. Do not act or rely upon the information and advice given in this publication without seeking the services of competent and professional legal, tax, or accounting counsel. Publication and distribution of this article is not intended to create, and the information contained herein does not constitute, an attorney-client relationship. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment or strategy is suitable for a particular investor. It should not be assumed that any investments in securities, companies, sectors or markets identified and described were or will be profitable. All information is current as of the date of herein and is subject to change without notice. Any views or opinions expressed may not reflect those of the firm as a whole.

Any projections, targets, or estimates in this report are forward looking statements and are based on the firm’s research, analysis, and assumptions. Due to rapidly changing market conditions and the complexity of investment decisions, supplemental information and other sources may be required to make informed investment decisions based on your individual investment objectives and suitability specifications. All expressions of opinions are subject to change without notice. Clients should seek financial advice regarding the appropriateness of investing in any security or investment strategy discussed in this presentation.

Certain economic and market information contained herein has been obtained from published sources prepared by other parties. Zacks Investment Management does not assume any responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of such information. Further, no third party has assumed responsibility for independently verifying the information contained herein and accordingly no such persons make any representations with respect to the accuracy, completeness or reasonableness of the information provided herein. Unless otherwise indicated, market analysis and conclusions are based upon opinions or assumptions that Zacks Investment Management considers to be reasonable. Any investment inherently involves a high degree of risk, beyond any specific risks discussed herein.

The S&P 500 Index is a well-known, unmanaged index of the prices of 500 large-company common stocks, mainly blue-chip stocks, selected by Standard & Poor’s. The S&P 500 Index assumes reinvestment of dividends but does not reflect advisory fees. The volatility of the benchmark may be materially different from the individual performance obtained by a specific investor. An investor cannot invest directly in an index.