3 More Critical Tests to U.S. Economic Resilience

For the better part of two years, the U.S. economy has been hobbled, troubled, unbalanced, and destined for recession—by the media and many economists’ telling.

But data tells us that the U.S. economy has been resilient.

Most readers are aware of the numerous headwinds that have challenged economic growth recently. Inflation soared past 9%, interest rates marching higher with aggressive Fed tightening, regional bank stress that tested the financial system, the threat of a debt ceiling calamity, and the list goes on. Pundits have yet to cease worrying and warning of the U.S. economy’s imminent downturn.1

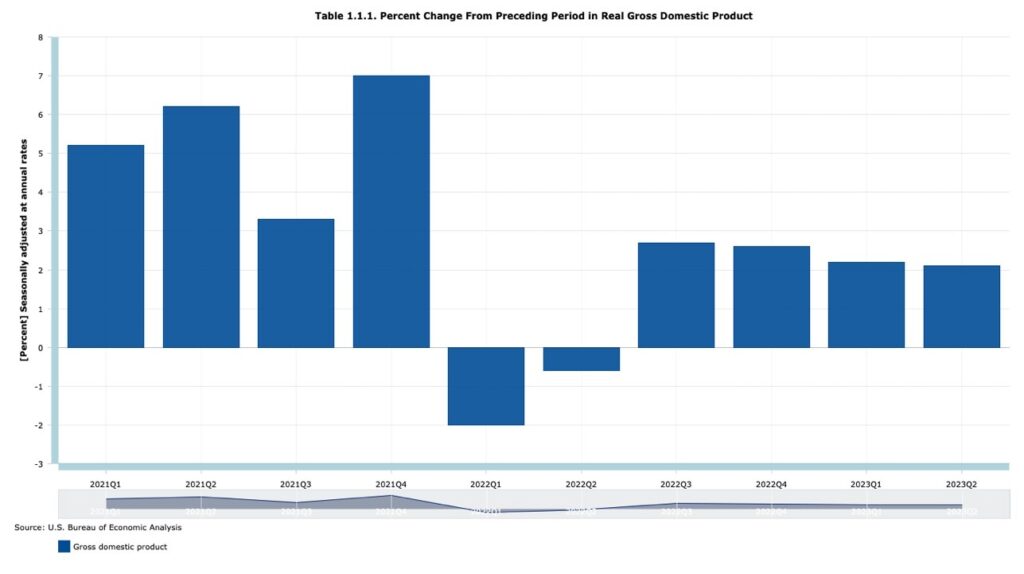

And yet, the U.S. economy has kept growing. We know that real GDP turned negative in Q1 and Q2 2022, but not necessarily because of a collapse of demand or actual output. Trade deficits, falling government spending, and plummeting inventory investment (following Q4 2021’s significant inventory build-up) played key roles in 2022’s negative GDP prints. This is arguably why the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) decided not to characterize it as a recession.

U.S. Real Gross Domestic Product (% Change from Preceding Period)

Heading into the end of the year, new warnings are emerging about the fate of the U.S. economy. This time, it’s the quadruple threat of the auto workers’ strike, the resumption of student loan payments, rising oil and gas prices, and a government shutdown. If one of these factors doesn’t sink the economy on its own, the argument goes, the aggregate impact of them will.

Let’s take a look at these ‘critical tests’ one by one.

First is the auto workers’ strike. The concern here is that work stoppages will hurt the inflation fight via higher car prices (which could then result in higher rates), while also dinging overall economic output. I’m not convinced either will happen.

A worker strike that lasts a long time is certainly not a positive outcome. But it’s important to note that it would not shut off U.S. output completely, as there are many foreign-owned and non-UAW plants across the country. Strikes would also not affect production across Mexico, Asia, Europe, and the rest of North America, which I would argue tempers the inflation impact. What’s more, all new cars make up just 4% of the U.S. CPI basket, which means price pressures should not have a disproportionate effect on overall inflation.

This is not to say that worker stoppages will come without pain. I think if we were to look at the impact on local economies and state economies where many major plants are located, there could be enough impact to turn output negative for the quarter in those states. The national economy, however, is too diverse for the U.S.-based, UAW-powered auto market to sink, in my view.

Next is the return of student loan repayments, effective October 1. By some estimates, loan repayments will divert about $100 billion from American’s pockets over the next twelve months, which is money that could have otherwise gone to spending on goods and services. The timing of the payments could be meaningful too, coming just a month before the holiday shopping season kicks into high gear.

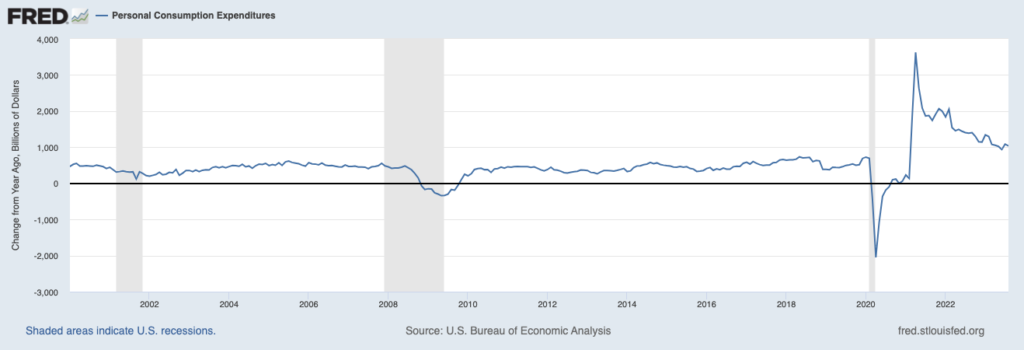

While $100 billion seems like a big number, it is very small relative to the $18 trillion U.S. consumers spend each year. It’s also worth noting that the average student loan payment before the moratorium was $265, which is not likely to break the bank for most U.S. households. According to the New York Federal Reserve, the median student loan balance at the end of 2021 was $18,767, and about 60% of households owed less than $25,000. Overall, analysis suggests that student loan payments could subtract about 0.8% from consumer spending growth in Q4, which would only slow it to 1.4%.

U.S. Household Spending Remains Strong (Change in Spending from a Year Ago, $Billions)

The final test to the U.S. economy is higher oil prices. The economic impact of higher oil prices was the subject of my column last week, so I won’t rehash my argument here. But the overarching point is that consumer spending on gas – as a percentage of total disposable income – is quite small for most households. If a household spends $400 a month on gas and that number moves up to $450 or even $500 with higher prices, I don’t see that moving the needle too much on total spending.

Bottom Line for Investors

The one ‘test’ I left out of my commentary above was a government shutdown, which has been cited as an economic concern but was also resolved as I was researching and writing this column. To be fair, however, Congress reached an agreement to only extend government spending for 45 days, so it won’t be long before we’re right back here talking about its impact on the economy. We’ll cross that bridge when we get to it.

Recent downside volatility in the stock market has many economists, pundits, and investors drawing a causal link to the ‘critical tests’ mentioned above. When market returns are negative, it’s often that investors look for more reasons to be negative. Economic concerns become potential economic calamities, which allude to more negative returns.

But it’s important for investors to remember that the economy has overcome much bigger obstacles, in my view, and remains in a resilient state. I would also call out that widely cited, discussed, and known fears like the ones I’ve detailed above generally don’t have much pricing power. The stock market has already digested their respective impacts. A final note to add is that from an investment perspective, August and September’s weaknesses don’t foretell October’s weakness – returns one month do not have any statistical significance on returns in the next month.

Disclosure

2 BEA. 2023. https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/?reqid=19&step=2&isuri=1&categories=survey#eyJhcHBpZCI6MTksInN0ZXBzIjpbMSwyLDNdLCJkYXRhIjpbWyJjYXRlZ29yaWVzIiwiU3VydmV5Il0sWyJOSVBBX1RhYmxlX0xpc3QiLCIxIl1dfQ==

3 Fred Economic Data. September 29, 2023. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PCE#

DISCLOSURE

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Inherent in any investment is the potential for loss.

Zacks Investment Management, Inc. is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Zacks Investment Research. Zacks Investment Management is an independent Registered Investment Advisory firm and acts as an investment manager for individuals and institutions. Zacks Investment Research is a provider of earnings data and other financial data to institutions and to individuals.

This material is being provided for informational purposes only and nothing herein constitutes investment, legal, accounting or tax advice, or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a security. Do not act or rely upon the information and advice given in this publication without seeking the services of competent and professional legal, tax, or accounting counsel. Publication and distribution of this article is not intended to create, and the information contained herein does not constitute, an attorney-client relationship. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment or strategy is suitable for a particular investor. It should not be assumed that any investments in securities, companies, sectors or markets identified and described were or will be profitable. All information is current as of the date of herein and is subject to change without notice. Any views or opinions expressed may not reflect those of the firm as a whole.

Any projections, targets, or estimates in this report are forward looking statements and are based on the firm’s research, analysis, and assumptions. Due to rapidly changing market conditions and the complexity of investment decisions, supplemental information and other sources may be required to make informed investment decisions based on your individual investment objectives and suitability specifications. All expressions of opinions are subject to change without notice. Clients should seek financial advice regarding the appropriateness of investing in any security or investment strategy discussed in this presentation.

Certain economic and market information contained herein has been obtained from published sources prepared by other parties. Zacks Investment Management does not assume any responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of such information. Further, no third party has assumed responsibility for independently verifying the information contained herein and accordingly no such persons make any representations with respect to the accuracy, completeness or reasonableness of the information provided herein. Unless otherwise indicated, market analysis and conclusions are based upon opinions or assumptions that Zacks Investment Management considers to be reasonable. Any investment inherently involves a high degree of risk, beyond any specific risks discussed herein.

The S&P 500 Index is a well-known, unmanaged index of the prices of 500 large-company common stocks, mainly blue-chip stocks, selected by Standard & Poor’s. The S&P 500 Index assumes reinvestment of dividends but does not reflect advisory fees. The volatility of the benchmark may be materially different from the individual performance obtained by a specific investor. An investor cannot invest directly in an index.