Why are Interest Rates Rising So Quickly?

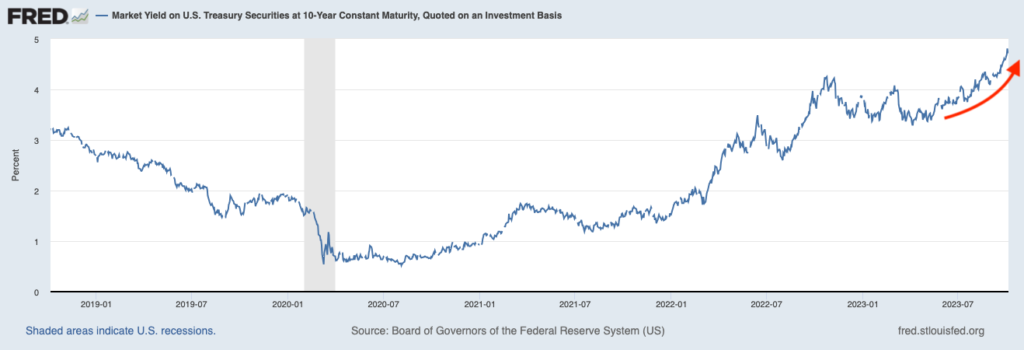

Many pundits in the financial media are summing up August and September in one sentence: interest rates went up, and stocks went down. This statement is true on its face: over those two months, 10-year Treasury bond yields rose 61 basis points while stocks fell -6.3%.1

Yields on 10-Year U.S. Treasuries Have Risen…

…While Stocks Have Declined

There is also good logic to the idea that as interest rates go up, stocks get pressured. Higher interest rates reduce the value of a company’s future cash flows, while also giving yield-seeking investors low-risk or even risk-free alternatives to stocks. For companies trading at elevated multiples (many of which are currently in the Technology sector), it makes sense that higher rates would make investors balk at paying a premium to own shares.

But I think it’s important to push back on the idea that every time interest rates go up stocks will go down. It is an oversimplification of how equity markets work, and it’s also just not accurate historically. There have been plenty of instances when interest rates and stocks were going up at the same time, and you don’t have to go back very far in history to find one.

In the second quarter of 2023, for instance, the S&P 500 rose +8.7% while yields on the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond rose by 28 bps. Interest rates went up, and stocks went up too. Ditto for the trailing 12-month performance of the S&P 500 and 10-year yields through June 30, 2023. Over that year, stocks climbed +19.6%, while the yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond rose by 84 bps.

I could devote many columns to why stock performance depends on more than just changes to interest rates. But the more important aspect of this story is for investors to pull back the curtain on why interest rates are going up. Doing so will give you more insight into equity market behavior now and in the future, in my view.

Generally speaking, long-duration interest rates tend to move higher for one or both of the following reasons:

- Inflation and/or inflation expectations are going up; and/or,

- Economic growth is accelerating or is expected to be stronger than expected.

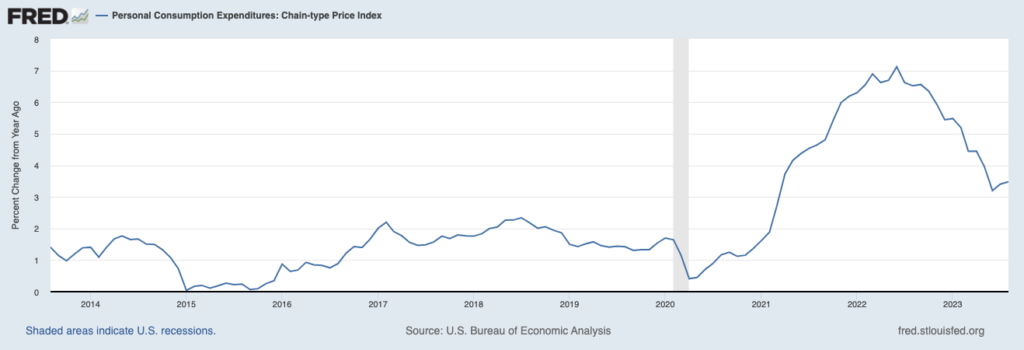

For now, I think we can rule out the inflation factor. In September, core CPI (which strips out food and energy) was up 0.3% from August and 4.1% year-over-year, an improvement from August’s 4.3% print. Importantly, when core CPI is looked at over a 3-month period, it increased at an annual rate of 3.1%, which is a substantial improvement from the 5% annual rate recorded in the spring. The gauge the Fed watches most closely, the headline personal consumption expenditure (PCE) price index, has also been in steady decline since last June:

PCE Price Index

Importantly, when core CPI is looked at over a 3-month period, it increased at an annual rate of 2.4%, which is a substantial improvement from the 5% annual rate recorded over the previous 3-month stretch. Inflation expectations have also returned to 2% compatible levels, which suggests that investors and consumers expect this trend to continue.

In my view, that leaves economic growth as the primary factor pushing interest rates higher. As of October 10, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow forecasting tool is estimating the U.S. grew at a +5.1% annual rate in Q3, and other data points to a U.S. economy that continues to defy growth expectations. The jobs market is one such data point – in September, nonfarm payrolls rose by a stout 336,000, the largest gain since January, and job gains were reportedly widespread across industries. Consumer spending also remains firm.

Stronger-than-expected economic growth should influence the currently inverted yield curve to steepen, which would mean either lower short rates or higher long-duration rates. The latter is what we’ve been getting.

Bottom Line for Investors

I do not want to leave out a third explanation for why interest rates have been rising, which has been getting some press lately. That is, the impact of U.S. debt and deficit spending.

Some in the media have posited that bond yields have spiked due to rising bond supply, as the U.S. runs a primary (ex-interest) deficit much larger than has been the case historically. As the Treasury issues more bonds to finance the deficit, some believe it is being met with falling international demand for U.S. bonds. This narrative could be accurate in some respects, but there is not enough data currently available to confirm it. The latest Treasury bond auctions show that the market is absorbing new issuance with little issue, and foreign holdings of U.S. debt are up over $500 billion since October 2022 and approaching an all-time high. This factor will be one to track, but I am not convinced it is a comprehensive explanation for why rates are rising.

As I was writing the column, Israel suffered a terrorist attack, which appears to be morphing into a larger and sustained conflict. We saw bond yields slip in the wake of the attacks, as investors—especially those in Europe and the Mideast—likely increased purchases of U.S. Treasuries in a flight to safety. Rising demand for U.S. Treasuries leads to rising prices and falling yields, which also helps explain the stock market’s short-term strength in the face of the terrorist attacks. We also saw some upward pressure on oil prices tied to production concerns from the region, but those pressures have since tapered off and did not have much effect on fixed income or equity markets—at least not to date.

Zooming back out, the bottom line remains that a stronger-than-expected U.S. economy is the main driver of higher rates, in my view. We’ll continue to watch the impact of oil production and its potential effect on energy prices—which can change the inflation equation—but for now we’re not seeing it as a major issue. While we would of course welcome a strong U.S. economy, it’s also true that “too hot” is not necessarily what we want to see at this stage. An overheating economy can beget inflation, which begets higher rates on the short- and long end of the curve. Higher rates alone cannot derail a bull market, but rising rates in response to rising inflation can.

Disclosure

2 Fred Economic Data. October 6, 2023. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS10

3 Fred Economic Data. October 10, 2023. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/SP500#

4 Fred Economic Data. September 29, 2023. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PCEPI#

DISCLOSURE

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Inherent in any investment is the potential for loss.

Zacks Investment Management, Inc. is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Zacks Investment Research. Zacks Investment Management is an independent Registered Investment Advisory firm and acts as an investment manager for individuals and institutions. Zacks Investment Research is a provider of earnings data and other financial data to institutions and to individuals.

This material is being provided for informational purposes only and nothing herein constitutes investment, legal, accounting or tax advice, or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a security. Do not act or rely upon the information and advice given in this publication without seeking the services of competent and professional legal, tax, or accounting counsel. Publication and distribution of this article is not intended to create, and the information contained herein does not constitute, an attorney-client relationship. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment or strategy is suitable for a particular investor. It should not be assumed that any investments in securities, companies, sectors or markets identified and described were or will be profitable. All information is current as of the date of herein and is subject to change without notice. Any views or opinions expressed may not reflect those of the firm as a whole.

Any projections, targets, or estimates in this report are forward looking statements and are based on the firm’s research, analysis, and assumptions. Due to rapidly changing market conditions and the complexity of investment decisions, supplemental information and other sources may be required to make informed investment decisions based on your individual investment objectives and suitability specifications. All expressions of opinions are subject to change without notice. Clients should seek financial advice regarding the appropriateness of investing in any security or investment strategy discussed in this presentation.

Certain economic and market information contained herein has been obtained from published sources prepared by other parties. Zacks Investment Management does not assume any responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of such information. Further, no third party has assumed responsibility for independently verifying the information contained herein and accordingly no such persons make any representations with respect to the accuracy, completeness or reasonableness of the information provided herein. Unless otherwise indicated, market analysis and conclusions are based upon opinions or assumptions that Zacks Investment Management considers to be reasonable. Any investment inherently involves a high degree of risk, beyond any specific risks discussed herein.

The S&P 500 Index is a well-known, unmanaged index of the prices of 500 large-company common stocks, mainly blue-chip stocks, selected by Standard & Poor’s. The S&P 500 Index assumes reinvestment of dividends but does not reflect advisory fees. The volatility of the benchmark may be materially different from the individual performance obtained by a specific investor. An investor cannot invest directly in an index.